Syd Field: "Screenwriting is finding places where silence works better than words"

Veteran Hollywood screenwriter Syd Field held a two-day workshop for wannabe writers in London’s Bloomsbury last weekend (12th/13th May), in association with Moviescope magazine. The event drew in participants from far-flung lands: “there are nine different countries represented here today,” as the man himself said. Suchandrika Chakrabarti joined them.

Veteran Hollywood screenwriter Syd Field held a two-day workshop for wannabe writers in London’s Bloomsbury last weekend (12th/13th May), in association with Moviescope magazine. The event drew in participants from far-flung lands: “there are nine different countries represented here today,” as the man himself said. Suchandrika Chakrabarti joined them.

Syd began the course with a short biography. He started his career in documentary filmmaking and network TV, before moving into literary and film criticism for magazines. After a few years of reading screenplays for production companies, he was invited to teach at Sherman Oaks College in Hollywood, alongside someone called Paul Newman teaching acting… Just prior to holding the workshop, Syd had been in India, working as a consultant on the BAFTA-nominated film, PK5, with Rakyesh Mehra.

As he put it: “There’s no way I can teach you to write anything – what I can do is show you how to write a successful screenplay.” Ominously, he added, “When you sit down to write your screenplay, you’re going to hear my voice in the back of your head.”

Syd quoted José Rivera, who directed The Motorcycle Diaries, to drive home his point about structure: “Screenwriting is like building furniture. It’s a craft… the audience never sees the machinery.” "Screenwriting is like building furniture. It's a craft... the audience never sees the machinery," meaning that the devices available to the screenwriter, such as Syd’s three-act paradigm (more of which later), gives a foundation upon which to build the text, but must not be made apparent to the audience, risking the destruction of their suspension of belief.

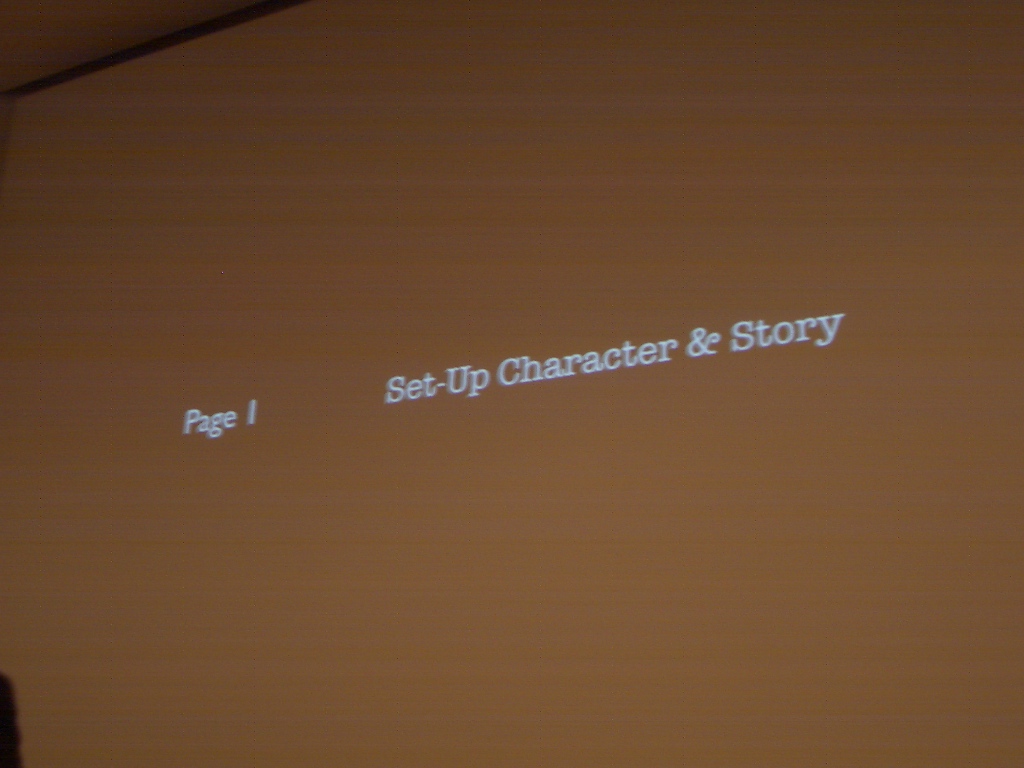

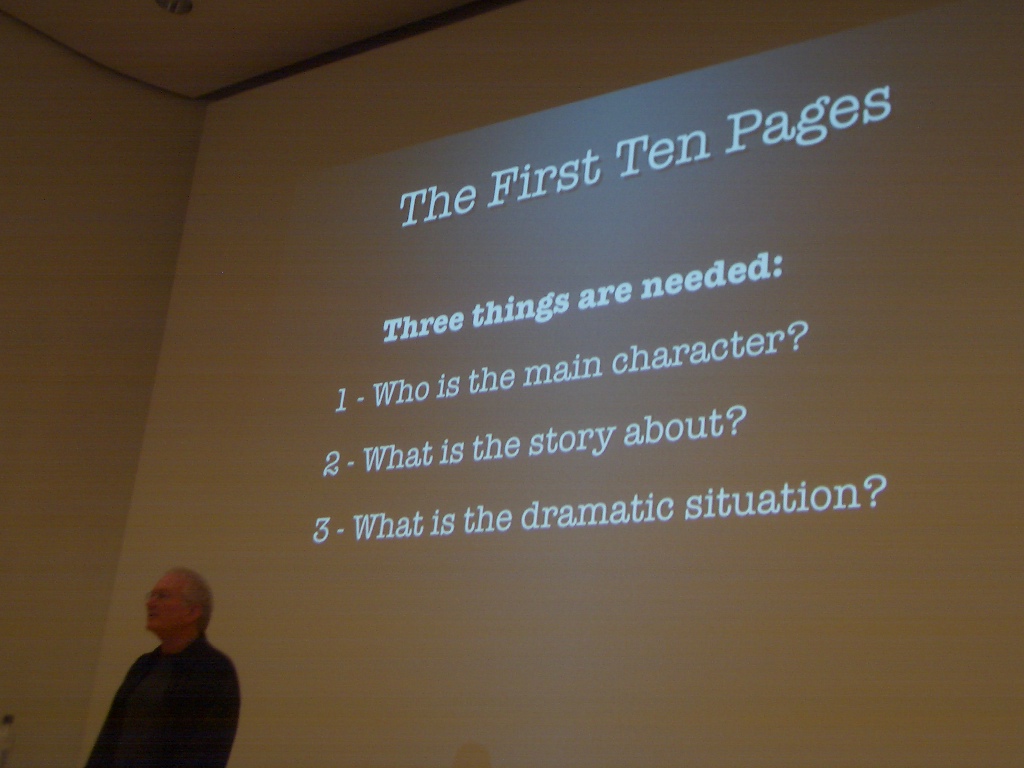

So, onto the details. In a general overview, the average screenplay is 120 pages, with one page equating to one minute of screen time. Acts one and three should be around 30 pages, with act two dominating at 60 pages. There’s also some stuff about plot points and midpoints but Syd explained them with a diagram, so this article probably cannot do the theory justice. Suffice to say that there ought to be moments of dramatic tension / incidents that move the plot along at the end of each act, and in the very middle of the screenplay, at the midpoint of act two. Syd emphasised that it was important not to get too hung up on the numbers, although some audience questions suggested that it was too late for that…

In talking about structure, Syd also uses well-chosen film clips, from his favourites The Bourne Supremacy and Seabiscuit (when pressed, he admitted that choosing between them was like selecting a favourite child), plus Little Miss Sunshine, Sideways and Thelma and Louise. In fact, the movie snippets proved so tantalising that some of us had to rush out and see the rest of the movie after the first day of the seminar ended (by the way, go and see Little Miss Sunshine, it’s good).

Apart from these, however, Syd’s use of imagery adds to his explanation of the importance of structure in screenwriting. He compares the flexibility of structure to “a tree bending in the wind” (for those in the audience worried about 19-page first acts being too short), and the invisibility of the all-important writer’s tool as “an ice cube melting in water.” The structure is made of the same stuff, but now you see it (when writing), and now – when watching the finished product – you don’t.

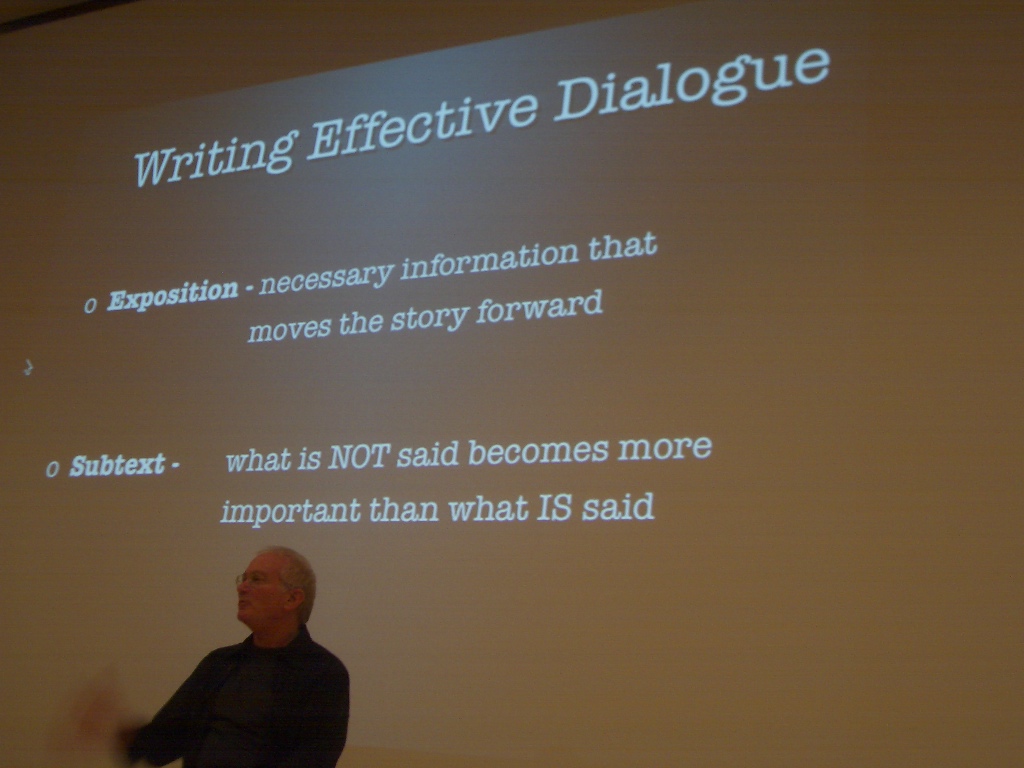

This distinction between the writer’s and the audience’s viewpoints was drawn out further when Syd said that "the screenplay is a reading experience before it is a visual experience." "The screenplay is a reading experience before it is a visual experience.” To that end, the first draft of the text needs to contain enough direction and other detail so that the reader (hopefully a powerful and helpful producer) can imagine the film as s/he reads. When the script makes it to filming however, much of this details has to be stripped out, to allow the director and actor room for interpretation.

As Syd commented: “You’re not going to tell the director how to do the job, even if you’ve written the thing.” Quoting the Bhagavad Gita, Syd exhorts us to not “be too attached to the fruits of [our] actions.” Write it and let it go is the message here. In comparison to, for instance, novel-writing, screenwriting demands collaboration, and, as Syd points out, sometimes the finished product can veer so far from the original dream that the writer asks for their name to be taken off the credits. He quotes Stephen King, a novelist with great experience of the adaptation process, on the difference: “apples and oranges; both delicious, but very different.”

As Syd put it, the difference between novel-writing and creating a screenplay is the visual dimension, which makes it possible to literally show rather than tell; it is "finding places where silence works better than words.” He illustrated this point, aptly, with a clip from Little Miss Sunshine, where a character who had taken a vow of silence erupts into a furious tirade against hs family. The most telling moment of the scene is a wordless gesture from his young sister.

“You have to get it out of you, because otherwise it is just kicking around and kicking around inside you.”

The two-day workshop ended on a discussion about re-writing. “When you sit down and face a blank sheet of paper, it’s pretty intimidating,” Syd explained, a feeling well known to anyone who has tried to put finger to keyboard (or pen to paper for the traditionalists). Screenwriting is a process of writing and re-writing, we are told, of the writer looking at his or her original intention, the script as written, and the degree of overlap. The process of revision is trying to bring the real and the imagined work closer together.

The audience included screenwriters, producers, directors, actors and those who were just about ready have a go. The seminar was generally seen as a great way to crystallise ideas, and shape written pieces into something that just might sell. As Syd confessed, all writers have this in common: "You have to get it out of you, because otherwise it is just kicking around and kicking around inside you."

For more information, please see Syd Field’s website.

To contact the author: