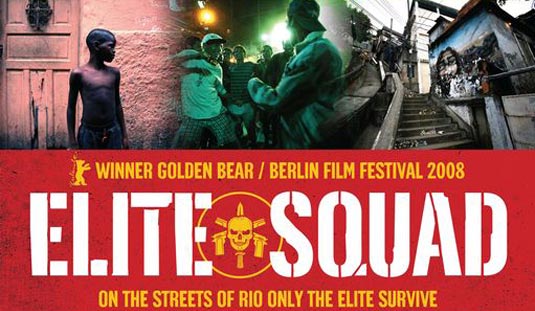

Elite Squad vs. City of God

As ever, there will be spoilers

As ever, there will be spoilers

Elite Squad has its UK DVD release tomorrow

Rio de Janeiro, 1997. The Pope is about to visit. Some doofus has put him up right next door to a notorious favela. The Special Police Operations Battalion (BOPE) have to clean it up before he gets there. So we get to take a look at a Brazilian slum through the eyes of the supposed law enforcers.

Where City of God, despite the bloodshed and endless vendettas, is essentially a nostalgic, sometimes humorous, look back by a boy made good, Elite Squad is an unflinching morality tale from which no one emerges unscathed, least of all the average middle-class viewer with an "occasional use only" attitude to drugs. Unlike City of God's Rocket (Alexandre Rodrigues), the narrator of Elite Squad continues to contend with the favela's problems, and is far more cynical. He has reason to be.

The BOPE was formed in 1978 to combat crime in the favelas, and the nature of their job is basically continual warfare. They don't have an easy job, and they don't take a gentle approach towards it.

Brazil’s police forces use violent and repressive methods that consistently violate the human rights of a large part of the population. Thousands of people have been killed by elements within Brazil’s military police; many have been unarmed and presented no threat. Before the Baixada Fluminense killings, four high-profile massacres had shocked the world: unarmed detainees in São Paulo’s Carandiru detention centre in 1992; children sleeping on the steps of Candelaria Cathedral in 1993; favela dwellers in Vigário Geral in 1993; and land activists in Eldorado dos Carajás in 1997. Countless other killings have gone unreported. Official statistics show that in 2003, police in the states of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo killed 2,110 people...

(Amnesty International report)

José Padilha's 2002 film, Bus 174, is rooted in the 1993 Candelária massacre. It portrays a survivor of the killings growing up to mount an bus hijacking himself; all of it based on the true story of Sandro Rosa do Nascimento. Similarly, with Elite Squad, "the question of the movie", as Padilha says in an interview included on the DVD, "is: 'What is the social process that creates these [corrupt cops]?"

Elite Squad is narrated by the weary Captain Roberto Nascimento (Wagner Moura; is the character's name based on Bus 174?), who is looking forward to retirement. His wife is about to give birth, he has drink and drug addictions and his panic attacks have led him to regular psychiatric sessions - not an unusual move for a BOPE cop. Nascimento is a likeable character, but, while rooting for him to get that peaceful family life he wants, we also watch him torture suspects. He is our guide to the favela, as Rocket was in City of God, but the difference is that Nascimento has been severely tarnished by his surroundings.

So Nascimento has to choose his replacement, and it's between André Matias (André Ramiro) and Neto Gouveia (Caio Junqeira). It's a battle of intelligence (André) vs. passion (Neto). You'll quickly pick up which one's the likely winner. As Nascimento puts it: “Neto was the hungriest for blood;” not the soundest basis for a long career, even with the BOPE. However, neither man remains untouched by the horrors of everyday working life in the favelas.

Elite Squad invites comparison with City of God not just because they are both Brazilian favela movies, but due to the involvement of go-to-guy screenwriter Bráulio Mantovani in both, and their depiction of outsiders. Padilha expressed gratitude for Mantovani's expertise in the DVD interview - the latter was nominated for an Oscar in 2004 for adapting the City of God novel for the screen. Mantovani was essential to the transformation of research into film script.

It gets more interesting when you look at how each film directly involves the audience. City of God is the reminiscing of a now successful photographer, who got his big break after photographing the bullet-riddled corpse of a local favela villain, Li'l Zé. Rocket's access to the drug gangs has already made him useful to the local newspaper - the journalists are too afraid to get so close. He again acts as a tour guide for the film's audience. Literally building his career upon the bodies of his peers, Rocket's journey must also be seen as a metaphor for the filmmakers. For what else is making films (or art; or writing) but a middle-class pursuit, completely closed off to the inhabitants of a favela, who are at the very bottom of the food chain?

Just as the present-day Rocket shows us something alien and exotic, so he once appeared to the white, educated journalists who were eager to use him. When the paper publishes photos of Li'l Zé without Rocket's consent, he fears for his life and states that he can't go home. A female journalist takes him in for the night and is amused by Rocket's wonderment at her warm shower - all he's had to date is a constantly-refilled kettle. Her eagerness to get him into her bed exposes her fascination with this rare new creature - a real boy from the favela! So begins Rocket's escape and social ascent. The middle class is the answer to one boy's problems, but the cycle of violence back home continues.

Filmmakers' keenness to put non-actor favela kids in their films has led to a lucky few achieving this dream in real life:

In exposing the gritty reality of Rio's favelas, Elite Squad and City of God may not have done much for Rio de Janeiro's image as a tourist paradise. But the films have highlighted a more positive phenomenon - a new generation of young, mostly black actors born and bred in the city's impoverished outskirts who little by little are starting to break into Brazilian TV and cinema, a world previously reserved for either the wealthy or the white.

Yes, a good thing. But, unlike the wealthy white counterparts, their new careers demand the same price that Rocket's did: continually returning to the scene of your troubled past and portraying / capitalising on the continuing warfare and deprivation. What, in the end, does the audience really do to change anything?

It depends on who's watching:

Even before the film was officially released, millions of people, from the southern metropolises of Rio and São Paulo to relatively isolated Amazon cities such as Manaus and Belém, scrambled for pirate copies, triggering a national debate about urban violence and drug use that dominated the front pages for months. When the film finally hit the big screen in October 2007, Rio's police force took its director, José Padilha, to court, accusing him of tarnishing the organisation's reputation, and then threatened to throw him in jail, until Rio's governor intervened in his defence.

(The Guardian)

So Padhila's depiction of police brutality was vindicated. That is something. He isn't so impressed by himself, though:

So, the film didn’t change anything and I don’t see it changing any time soon. My perspective on this is that the best way to understand it is to understand the rules of the game. If you want to understand the behaviour of poker players, you can only understand them if you learn the rules.

His film tells us that we are all part of the game.

Therefore, Elite Squad includes the viewer in the system of misery that props up the BOPE and the drug dealers. Padilha clearly sees this point as essential to the film, and expands upon it in the DVD interview:

I choose to do a provocation with this movie, because a lot of people… conceive the war, what’s going on, as a private war between drug dealers and policemen, as if the middle classes were not a part of this process.

[...]

If you buy drugs in Rio, and if it’s cocaine and marijuana, you are funding heavily-armed groups of drug dealers who control very poor communities in a very mean way. Drug dealers are not nice to their own people.

[...]

A cool newspaper writer who does a little joint before writing a review… maybe you’ve written several reviews critical of violence in Rio and you never saw your own role in it, and now this film is pointing at you and saying, ‘Lo and behold, you have something to do with it’."

A provocation indeed. The film extends the blame beyond the casual drug user to upholders of the political systems that pay the cops so little and leave them open to bribes: politicians and, ultimately, the voters, for not trying harder to change things. As Padilha says elsewhere, "If you’re in New York and buying marijuana, for instance, you’re probably not creating a lot of violence in New York itself, but you may well be in Colombia where the drugs have come from. So, we’re talking about a universal subject that has relevance for us all."

This universal subject unites City of God and Elite Squad, but Padilha's film is far more violent and difficult to watch. It tells you much more, though, about the hidden systems that keep the inter-dependent favelas, drug dealers and law enforcers afloat.

Elite Squad is released on DVD in the UK on 26th January 2008

To contact the author: