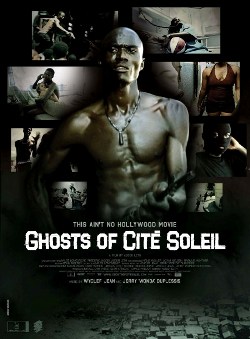

ASGER LETH: risking everything to make GHOSTS OF CITE SOLEIL

“We were being chased to the airport by a bunch of chimeres, and people were being shot on the streets. Just at the airport, in front of the terminal, a guy got shot right when we arrived.”

I don't know if Denmark’s Asger Leth has ever actually said he would die for his art. Actions speak louder than words, though, and while making the controversial documentary Ghosts of Cite Soleil, Leth often wondered if he and his co-director/ cinematographer, Milos Loncarevic, would live long enough to finish the project. To get film in the can they risked going home in a box.

Leth was determined to make an “amazing film” that tested the boundaries of the documentary form; it would be real life, and yet play like a movie that put viewers on the edges of their seats.

“I think documentaries have forgotten about filmmaking, a lot,” he says. “There’s a lot of talking heads, and a lot of intellectuals arguing, BBC style, and I think that’s journalism, TV programming, it has nothing to do with filmmaking. So, I figured I wanted to bring some more storytelling back into documentaries. I wanted to make a personal drama, with strong, complex characters, with hopes and dreams, up against the wall, facing an enemy. I was very, very clear about getting that.”

He found what he was looking for in Cite Soleil, a sprawling, lawless, gang-ridden slum in the Haitian capital, Port-au-Prince, that the UN designated “the most dangerous place on earth”. It is just a two-hour flight away from Miami, but it is a wretched place where around 300,000 people live in abject poverty. Few survive past the age of 50, many dying from disease or violence. Children play among the piled-up rubbish and open sewers, bleak futures ahead of them. “The value of life in Haiti, and especially in the slum, is nothing,” says Leth.

He knows Cite Soleil well, having visited it numerous times during the decade that his father, acclaimed filmmaker Jorgen Leth, lived in Port-au-Prince. Conditions have got much worse since then, he says. After Jean-Bertrand Aristide - Haiti's first freely elected president in 200 years of independence - was deposed in a coup d'etat in 1991, armed gangs started to appear.

The early ones were affiliated to an anti-Aristide political movement called the Front for the Advancement and Progress of Haiti (FRAPH). “They were death squads,” says Leth. “When Aristide came back to power, with the help of the Americans, the Americans then started emptying prisons full of Haitian illegal immigrants, gang members, in the States. Some of them had grown up there and didn’t know Haiti. So all of a sudden they’re chained together, put on planes and flown to Port-au-Prince, and it's ‘Have a good life’. Then, of course, they continued their gang life down there.”

As Aristide’s position became ever rockier, the president enlisted armed gangs known as chimere (literally ghosts) to violently quash the opposition. “In the last five years of Aristide,” says Leth, “because they became so powerful, the chimere became kings of the slum. It got so dangerous that ambulances wouldn’t go in there. There was no police anymore, nothing. It became a no-go zone.”

Astonishingly, Ghosts of Cite Soleil was filmed inside the slum leading up to, during and immediately after Aristide was overthrown a second time at the beginning of 2004. As Leth was making a documentary, he did not have absolute control over events. However, Haiti’s history is so “cartoonishly” predictable – “it’s like it is running on a bad track on a bad record to the point that it becomes self-fulfilling” - that you do not have to be Nostradamus to see where the country is heading at any time. “There was a rebellion coming to town," recalls Leth. "There was a president who was in big trouble and couldn’t get any help. He had his gangs working for him and I was convinced that the president was going to leave the country eventually, or be thrown out, which meant that the gang leaders would be facing the price to pay. I was so convinced they were probably going to die, these guys. So I knew that the dramatic structure would probably pan out. That’s what I gambled on.”

"These guys" were Bily and 2Pac (real names James Petit Frere and Winson Jean), brothers who were also rival gang leaders on opposite sides of the Aristide question. Leth got unprecendented access to the siblings and their world thanks to Lele (Eleonore Senlis), a French relief worker, and Milos Loncarevic, a Serb who grew up during the Balkan War and was now taking stills in the slum. We learn that 2Pac, although he still worked for Aristide, had fallen out with his paymaster after he put him in jail. Now he vocalises his opposition in rap songs, and dreams of leaving Haiti to pursue a music career. Bily, meanwhile, is an Aristide loyalist, and wants to enter politics to help his people. There is little doubt that both brothers have blood on their hands.

Leth gets up close and personal with them. He films them playing with their kids, smoking dope, wielding guns, threatening to kill people, musing fatalistically about their futures, and even falling in love with Lele. 2Pac, at one point, gets to play some of his music down the phone to Haitian ex-pat and former Fujee, Wyclef Jean, who helped score the film.

Some critics have accused Leth of being seduced by his subjects. They say he lost his objectivity. “People attack me for just hanging out with the gangs without condemning them,” he says. “But I’m not condoning them either, because I do think they’re thugs and killers. But I wanted to show them as human beings, first of all, because they are not the disease. They’re the symptom of a disease that’s not being treated. They pick up a gun because they have nothing. I’m thinking to myself, ‘If I grew up in Cite Soleil, would I pick up a gun?’ I think I might.”

The film’s style raises another question about the blurring of the line between exploration and exploitation. Leth argues that he did not exploit anyone because he also had a lot to lose. “Of course I’m not naïve; I’m always the white guy, I can always leave. But at the same time I did risk my life, and the life of everybody telling their story. They really wanted their story told because nobody else would go in there and tell it. They were convinced they were going to die.”

Financially too he staked everything on Ghosts of Cite Soleil. “I borrowed all the money to shoot the film in the bank and I had no way of ever paying it back if the film didn’t work. What if the story stopped halfway through? I would probably have had to move to Jamaica and become a bartender.”

The entire project was a gamble and might not have happened at all if Leth's marriage had not collapsed. “I had just gotten divorced,” he says, “and I was, like, ‘Fuck it all’. So I went down to Haiti and just started shooting.” It was a harrowing experience and he learned a lot about fear. But it was not just City Soleil that was dangerous. During the rebellion, Port-au-Prince generally was under siege by the gangs and the filmmakers would get shot at as they tried to drive through burning barricades. For a while there were no planes out, as the chimere had threatened to shoot them down as they flew over Cite Soleil. Journalists were being smuggled from their hotels to safer locations in the backs of cars. “There was like a pre-Rwanda kind of feeling,” recalls Leth. “Everyone, more or less, was eventually staying at the same place at the top of a mountain. And there was a feeling among everybody that the gangs were getting closer and closer. During that time we had to keep shooting our film and go down into Cite Soleil, so that whole thing was pure madness.”

When flights resumed, he got the first plane out. “We were being chased to the airport by a bunch of chimeres, and people were being shot on the streets. Just at the airport, in front of the terminal, a guy got shot right when we arrived. It was really hairy. So I got on the plane and I was like, ‘I’m never going back.’”

But he had to. When Leth returned to Denmark to edit the footage to “see if it fulfilled the dreams [he] had of making a different kind of documentary”, his suspicion that he needed more to complete the story was confirmed. “I knew for sure I couldn’t finish the film with what I had,” he says. “I had to keep going.”

Ghosts of Cite Soleil is released to buy on DVD on October 22.

© Stephen Applebaum