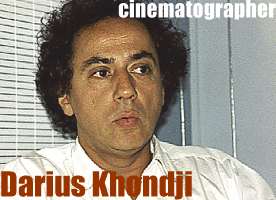

| netribution > features > interview with darius khondji > page one |  |  | Darius Khondji is one of the most celebrated cinematographers of contemporary cinema and when I got the chance to interview him at the Edinburgh festival I was beside myself with a mixture of trepidation and joy.

Khondji's list of credits are not as consistently brilliant as some of the world's DP's but when you look at the films again, and not even that closely, you see the work of an incredibly talented man with a true gift of the eye. In Delicatessen (1991) there is clear evidence of the French poetic realist cinema of the 1930's. With Jean-Pierre Jeunet again in City of Lost Children (1995), there is an aesthetic comparison with the grotesque tones in the paintings of German expressionist Otto Dix. He is perhaps best known for his bleak, colour-noir effect in David Fincher's, Se7en (1995), a film with which any film afficionado or regular cinema goer will always remember the cinematography especially. Suspected influences could be drawn from Gordon Willis' lighting of Klute (1971) but Khondji itterates that his one true influence, his 'friend' that never leaves his side is a book by Robert Frank called, The Americans. His comments about the filming and consequent box office reception of Danny Boyle's, The Beach (2000) are particularly interesting and they best reflect his passion for the perfect image. One question I regret not asking him (time restraints!) was what it was like working along side his mentor, the great cinematographer Vittorio Storaro in Bernardo Bertolluci's Stealing Beauty (1996).

One might well go on but it would be simpler to simply list the films that he has left his mark upon at the end of the interview. However, I have often wondered how he has not been nominated for more than one Oscar nomination (Alan Parker's Evita, 1997) or, indeed, been awarded an Oscar at all. | | |

| | by nic wistreich |

| photos by nic wistreich|

| in london | | | | |  | | | |  | | | | | I read that you were sneaked into King Kong as a kid?

Where did you read that?

In an interview in Face to Face.

Yes, that's true. I was dressed up by my parents. When I was 12 years old I became fascinated by Vampire and horror movies and my parents and my sister recognised. When King Kong came to our town in the suburbs of Paris I was too young to see it. So my sister who was a 20 year art student and my mentor dressed me up to look older with the help of my mother. Anyway, we managed to get in to the cinema but when the opening credits began to roll the police came in to check up and they found me. Even though I looked a little older than my age, they argued with my mother about my age but because I had no proof they told me I had to leave. I was terribly disappointed and frustrated at missing the film. That frustration as a 13 year old made me want to lay my hands on as many horror films I could find. I saw all the B-movies, all the Hammer horrors, all the Dracula films that I could see, and that was a lot of films, I became a film fan through this path. Then my sister took me to the Franch Cinemateque. This is where I discovered the 'family of cinema', its totally free of boundaries or frontiers and people were there from all over the world. In the 70's it looked like an Aztec temple with huge pillars, an enormous screen and all built in the concrete, fascist style of the time but for us it was monumental. I discovered film there and must have watched thousands of films from the birth of cinema and from all over the world.

Did you go to UCLA from there?

No, I started to direct my own short films and bought my friend's father's 8mm camera at 13, this was before the Super-8 came out. I made Dracula pictures with myself as Dracula, shooting when I wasn't starring. Then I started to make some short surrealist films in the Bunuel style with my best friend Louis Becker, the grandson of the pioneer Jacques Becker. Then I decided to America to study film because you needed a scientific baccalaureate to attend the very technical French film schools, I only had an art and a philosophical background and I was hopeless at maths and physics. I went to Los Angeles, then San Francisco for a short time and then my girlfriend at the time invited me to see New York before I started at UCLA. So I arrived in New York in a midnight snow-storm in the winter of '77/'78. New York just blew my mind like a character, like a great lady almost or like a modern art sculpture. The city was blanketed in snow and when I awoke in the morning there were people skiing down 5th Avenue, it was an incredible time to be there and there was no way I could leave or study or do anything anywhere else in the world except New York. So I stayed there and studied and met some people.

Which is where Scorcese went.

Yes, his teacher taught me, lovely man and a great teacher. He was someone that transmitted the passion of filmmaking and cinema, which is the most important thing for a student.

Were you always going to be a cinematographer?

No, I wanted to direct first. Little by little I realised that what I liked most about film was to create a mood for a story but not actually tell the story. | | | | |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | |  | | | |